Science Dimension volume 2 issue 3 June 1970

|

. |

| Melody of a musical composition as it is entered directly on the computer display (NRC) |

In almost all cultures, the earliest known forms of music were sacred and ritualistic. Secular music developed during the 10th century and with it established rules of musical form began to break down. Emphasis on individual genius characterized the 17th and two succeeding centuries, producing music's immortals.

However, the desire for change so prevalent in every area of life throughout the 20th century, has applied to the field of music as well, resulting in an inevitable search for something new: thus, new scales, rhythms, ranges, key relationships, even instruments, and with the advent of electronic music - a general break-away from conventional form. Technology, all the while, has interacted with music and played an integral part in the creative process.

Now engineers with the Radio and Electrical Engineering Division of the National Research Council of Canada, have developed a program package which allows a composer to write, modify and manipulate melodies while sitting at a computer display console. In this research, NRC is interested only in exploiting technology and not in composing music.

"Man has adapted himself enough to the computer," says Ken Pulfer of the Division's Data Systems Section. "It's time we started adapting the machine to man."

| . |  |

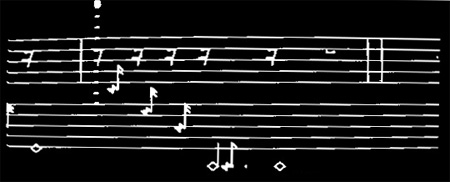

| Diagram showing creative interaction between user and machine. (NRC) |

So when free-lance composer Larry Crosley was called upon to produce the music for Carleton University's new film "The Johari Window", illustrating the dynamics of one person interacting with others, he had his first interaction with an NRC computer.

The 93-minute film opens and concludes with music composed by Mr. Crosley on NRC's computer-aided facility, with an additional six minutes comprising one of the five student-produced fictional segments. The segment is wild and free and the music enhances the sense of freedom of movement. There is a computer in one scene, and the composer decided the most appropriate music to accompany it should come from a computer.

The input interface of NRC's music package consists of two parts. One is a keyboard and positioning wheel which allows a melody to be entered in the form of notes, rests, and other musical symbols. While this is being done, one of the output interpreter programs presents to the composer a picture on a screen, which looks much like sheet music on which he can see his music being written on a staff. By means of the keyboard, Mr. Crosley can also enter control information into the melody. Commands which define attack and decay, key, and logical boundaries of portions of the melody are available. Loudness and speed are also parameters which can be defined, and individual notes can be marked for amplitude stress.

The constructing package also includes editing facilities which allows the composer to easily modify melodies. Any number of notes or control signs may be inserted, deleted or overwritten as the composer desires. The second input-output interface pair allows him to sketch on the screen an amplitude versus time curve which defines the waveform and thus, the timbre of the sounds to be created.

A third interpreter program takes the melody and waveforms just created and "plays" them through a loudspeaker in the form of live music. Constraints are imposed during both the construction and interpretive phases. The computer allows only notes with pitches on the chromatic scale to be entered, and produces only the corresponding pitch sounds. Time durations of notes are limited to multiples of the duration of a "thirty second note" for a given choice of "speed."

An arrangement facility is available which permitted Mr. Crosley to say, effect: "Play the first part twice with a slow decay and a mellow timbre; then play the second portion with a deep reed-like tone, followed by the first part again, one octave higher and with a very sharp decay."

|

. |

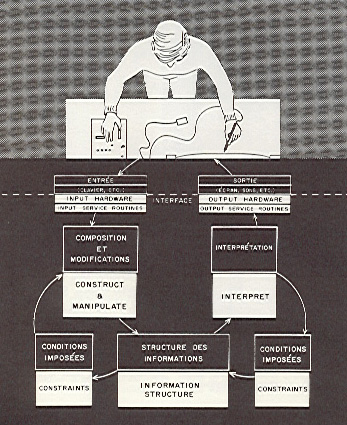

| Free-lance composer Larry Crosley constructs and modifies his composition with the help of NRC's computer-aided facility. (NRC) |

The composer at any time may name and store away melodies, timbres, and even arrangements that he likes, and recall and combine these later in other contexts. At no time was it necessary for Mr. Crosley to learn how to program the computer, or in fact, even to know how to operate it, other than through making some choices from names presented to him on the screen.

"It's another instrument", says Mr. Crosley, "an instrument that does fantastic things - things that musicians can’t do."

The computer-aided facility then the equivalent of pen, paper, musician and instrument. The composer, by means of the input interface (pen), constructs and modifies an embodiment of his idea (the composition) in the computer memory (the paper). The computer then translates this entity just produced into a form (sound) that the composer can appreciate and by means of the output interface (the musician and his instrument).

After hearing his creation, the composer may then modify it and listen to it again, and the process continues he is satisfied.

If the appropriate key words are changed, this is an equally good description of architectural or engineering design, the formulation of new mathematical models describing the physical world, or the writing and producing of a play.

The computer has brought a new dimension not only to the field of music but to other creative fields as well, as it offers the artist a stimulus to create in the form of the unexpected. If the response he receives to a given input is new and different, it may trigger a whole new approach.

F. V. Cairns, Head of the Data Systems Sectioin, emphasizes "that it must be understood research in this Section is aimed primarily at solving engineering problems. NRC is not involved in composing music as such. We are interested only in exploiting technology."

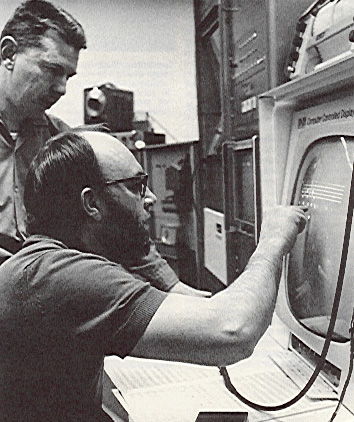

But as composers and others are the eventual users, the engineers in the Section require their comments in order to find out how useful the technology will be and how it should be developed.

"We encourage artists and composers like Crosley to use the machine," says Mr. Cairns, "as it is only from them that we can learn how the artist communicates with it."

Mr. Pulfer is attempting to find out what aspects of the system are common to the creative process in general and which ones are specific to a given type of creation, say, circuit design, architectural design, art, or music.

"Because the main objective of our research is the study of interaction between man and machine in a creative environment, we want to find a set of primitive operations from which the specific system components can be constructed. The setup at present is not oriented towards the production of high quality music, but is more of an experimental rather than production-oriented facility," he says.

| . |  |

| Ken Pulfer (right) of the Data Systems Section, explains the use of NRC's music package to Nil Parent, Professor-Composer at Laval Univesity's School of Music. Professor Parent is using the computer for research on the theoretical aspects of musical composition. (NRC) |

There are, however, limitations in the type of music and type of sounds which can be produced. They are imposed by the speed of the computer and the approach taken to synthesizing the waveforms within the machine. For example, at present the output is monophonic, and harmony cannot be produced "live" without sacrificing some other parameters such as tone quality. Such limitations, though perhaps serious to some composers, are of secondary interest in the Section, and presumably can be reduced to acceptable levels by a more powerful computer, and higher quality hardware.

On the other hand, the composer may point out that he finds it intuitively difficult to think of timbre or tone quality as being specified by a waveform on a screen, and that he would much rather communicate in a different sort of language. In such a case this would be a definite hindrance to creative activity.

"I missed the element of human expression in it," says Mr. Crosley, "but then, you don't expect that. You get striking effects with the instrument because of its capabilities and I want to work with it again."

One measure of the success of a facility for aiding creative activity is that if it is used by a number of different people, the results should reflect the character and weaknesses of the individual users, rather than the faults of the machine.

"On the whole", says Mr. Pulfer, "user reaction to date has been enthusiastic and we hope that some of the ideas generated may be useful to other users of computers in creative fields."

Reprinted courtesy of National Research Council of Canada