LAKE COMO: ROMANTIC BEAUTY

"I ask myself, Is this a dream?" So mused 19th-century American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow as he gazed in what must have felt like a trance across the shimmering water, almost, it seemed, unable to stand the power of the overwhelming spectacle of nature before him. He was standing on a shore of Lake Como, undergoing the same stunned reaction experienced by poets, artists, musicians and philosophers who stood there before and after him, for no other setting in Italy has ever responded so unerringly to the yearning state of mind that is romanticism. Judging by the flow of admirers, the lake still awakes hearts, and wonder too, especially after the alleged discovery of a mighty monster said to be lurking in its frigid depths.

It is in fact the deepest lake in Italy, at points plunging to 1,230 feet, although it is not the

biggest. Lake Garda is the largest, and next comes Lake Maggiore. Some thirty miles long,

with one hundred and ten miles of coastline, Como is certainly the most evocative of the

lakes. The ancient Romans called it "Larianus," which Roman politician Cato affirmed was

derived from the Etruscan for "superior in rank." It is a lake of creeks, small islands, tiny

harbors, little beaches and almost overabundant vegetation, its flanks carpeted with forests of

beech, birch and fir, ash, hazel and chestnut, and these forest blankets are almost everywhere

tucked in at the water's edge. It is a place, too, of vineyards, olive and lemon groves and

above all of flowers - of white heather and especially of trumpet-flowered rhododendrons that

fleck the banks of the lake with blazing patches of color.

The favored little "capital" for admiring and exploring it all has long been the idyllic small

township of Bellagio, right in the center of the lake, where its three "arms" meet. Set at the

foot of a hilly promontory, Bellagio has steep, cobbled alleys, fashionable hotels and lakeside

restaurants. It also commands spectacular views, to the north of often snow-powdered and

contemptuous Alpine peaks, the highest being Mount Legnone (7,827 feet), standing like a

sentry over the Garden of Eden to the south. During the hot summers, the lake is ventilated

by day by a pleasant breeze known locally as the breva, which breathes against the Mount. At

night, the breeze turns tall and comes back under another name, the tivano. The Romans

knew it, and many had villas on the lake, cool and welcome safety-valves against the stress of

political intrigue in the capital. But it remained just a lake - chiefly a communication

channel. Still hugging its western bank, for instance, is a twisting road near what was the

ancient Romans' key route of transit to northern Europe, later used in the opposite direction

by barbarian invaders and then by the Lombards, who settled in much of northern Italy.

Bellagio's lakefront.

Things more or less stayed like that until less than a couple of centuries ago, when Como ceased being merely a physical feature to become something else - a creation of the mind, a mental projection, intangible and unreal, a psychological discovery. What had happened? The answer: the Romantic Movement. It was partly a backlash against 18th-century rationalism, which saw man mainly as a creature of society. The individual came into his own - with a soul, too. As British critic Sir Ifor Evans once said of the Romantic poets, "They all had a deep interest in nature as spiritual influence on life.... In the poetry of all of them, there is a sense of wonder, of life seen with new sensibilities and fresh vision Lake Como was mirror and crucible of that vision, a fount of new experiences to which the romantic mind exposed itself - to scented breaths whispering a secret language, to evocative mists that shroud the lake in mystery, to the gentle thudding of unseen oars after nightfall, to the switching moods of the flighty lake, now all smiles and brightness, now all melancholy and gloom.

Here at Como was consummated the conspiracy between man and his surroundings, and the great poets, novelists and composers of the time struggled over the mountain passes to the lake to sense and celebrate the new accord. Lord Byron came; so did Robert Browning, Goethe and Heine and Stendhal. Tchaikovsky and Liszt followed suit, while Gioacchino Rossini and Vincenzo Bellini composed operas on its shores. Even peppery Mark Twain was moved to note: "As the music of vesper bells comes stealing over the water, one almost believes that nowhere else than on Lake Como can there be found a paradise of tranquil repose." Longfellow added: "I ask myself, 'Is this a dream? Will it vanish into air? Is there a land of such supreme and perfect beauty anywhere?' "

And at the turn of the century, one British traveler, Richard Bagot, was still reeling. He

speaks of "a scene of such romantic beauty as to create a momentary feeling of bewilderment,

an impression of unreality," and he finds that in the "soft Italian atmosphere" the lake exudes

"a dreamy, voluptuous charm." He described one scene that attracted him: "At nights, the soft

sound of cow-bells which the fishermen attach on floats to mark the position of their nets is

particularly attractive, and very picturesque is the effect of the boats, gliding under the shores

in the shallower water, with a flaring torch fixed in the prows, the light of which attracts the

fish, which are then speared."

A lake steamer in the days when steam engines were fueled

with wood, plentiful on the lake's shore.

Indeed, it is by boat that the lake today is best seen, by boats and hydrofoils that zigzag across it all day long, affording glimpses of deep caverns, coves invisible from the road, the bell towers of small Romanesque churches and sheer cliffs plunging downward into the water. You come upon cramped fishing villages fighting for space, private docks with their private worlds, and above all, magnificent villas that rise on the shoreline, regal and grandiose. The most admired of all is the Neoclassic Villa Carlotta, just outside Tremezzo, on the west bank, today almost the symbol of the lake, a huge mansion and splendidly planted park totally at one with its lush and leafy environment.

The villa is named after Charlotte of Nassau, daughter of Albrecht of Prussia, though as her

dowry it passed into the hands of her husband, a duke of Saxon. The house presides over a

steep and symmetrical English garden. Amid azaleas and camelias, beds of rare flowers and

hedges and terraces climb up to the dwelling from a circular clearing centered on a dolphin

fountain. Under three balustraded terraces, grottoes bubble with water from lesser fountains.

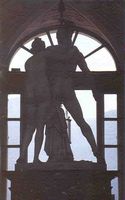

Inside the house, beneath mythological frescoes are renowned works of art, especially a

sensuous Love a Psyche, a creation that has emerged almost alive from the hands of the

Neoclassic sculptor Canova. But even Canova's forms of ecstatic youth fail to transcend the

peace and magic contemplated from the high windows. Behind the mansion, paths wind

through forests of azaleas, shady groves of ferns and multicolored mosaics of flowers in

bloom.

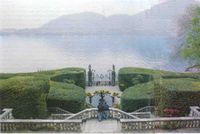

Villa Carlotta. Symmetry is the key to the formal elegance of the staircase in front of the villa.

Fanlike palms are just one of the exotic species in the fabulous botanical gardens of the villa.

The great entrance hall of the villa is a gallery that holds some fine Neoclassic sculpture.

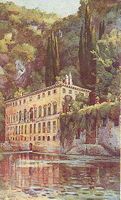

Without garden or visitors, and even without sun except for a few hours a day at the height of

summer, stands the most tragic and solitary villa of them all, the Villa Pliniana. Though both

of the ancient Roman writers, Pliny the Elder and the Younger, are from Como and are

known to have lived nearby, that is not where this villa gets its name. Villa Pliniana is on

exactly the same site where Pliny the Younger was baffled by a mysterious spring which

continues to confound experts today. As be wrote to a friend, the spring inexplicably turns

from trickle to flow three times a day. The villa is on the somber eastern shore of the lake,

and giant cypresses protect it from behind, like bodyguards holding back a craggy

mountainside that seems to threaten to nudge it into the lake. There it broods, lightened only

by a graceful porch of three arches let high up into its facade. It grew out of the blue-green

water of the lake in 1570 at the behest of one Count Giovanni Anguissola from Piacenza, who

was keen both to hide from assassin and to do penance after slaying the son of Pope Paul III.

He flung the mutilated corpse out of a window.

Villa Pliniana.

Murder, more public and more recent, is also linked to the sumptuous Villa d'Este on the

other bank, once a medieval cloister, then a palatial summer residence a cardinal had erected

for himself in 1568. Now it is one of the world's great hotels, sometimes known as

"Hollywood on Lake Como" because for many a year movie celebrities have been among its

well-heeled, mainly American, guests, from Mary Pickford and Greta Garbo, Zsa-Zsa Gabor

and Esther Williams to Sylvester Stallone and Sharon Stone. Set in ten acres of stylized

parkland, Villa d'Este is a gem of luxurious accommodations and impeccable landscaping,

with arbored byways and a Renaissance mosaic-decorated exedra and nymphaeum. One

owner, the young wife of a Napoleonic general had mock battlements made out of the rock

face overhanging one side of the park to keep her husband happy. And they still talk of that

gala party on a night in 1948 when a shot rang out. Fun-loving industrialist Carlo Sacchi fell

dead. Before everybody stood Pia Bellentani, a jealous mistress, grasping the gun.

Villa d'Este. It is set in a park on the lakeshore in Cernobbio.

A baroque exedra in the park of the villa frames a perspective

of a hilltop nymphaeum. An arbor shades the villa's lakeside terrace.

But the lake holds far grimmer memories. It was not always romantic. In the 16th and 17th centuries, it seems to have been a jostling mecca for witches and an arena for zealous churchmen who had many of them burnt to death. Como then kept a frontline watch against the infiltration of northern European heresy. The witches, it is told, kept magic formulas inscribed upon the skin of murderees. They advised anyone who wanted to discover who might wish him ill to burn old rags in order see his enemy's image through the smoke. Many confessions were wrung out of alleged witches and other persons for supposedly consorting with the devil or dealing in magic. A priest confessed to carving symbols on bones. Women from lakeside Lezzeno said they attended witches' Sabbaths after scratching a circle in the earth and killing an animal within it. One admitted she had danced with a male devil with the feet of a goose and a furry hands. Another said she stamped upon a communion wafer. If saved from death at the stake, witches were ordered to wear a red dress with yellow stripes for three years as a sign of shame. As the 20th century began, the 1ake was a haven, instead, for smugglers, driven to their trade by poverty and often working hand-in-hand with the customs police.

As for monsters, one humanist, Paolo Giovio, records seeing them sunning themselves near the shore, fearsome-looking creatures with scaly skin, so big and heavy that no net could hold them. Now a Milanese veterinary surgeon and expert in cryptozoology, Maurizio Mosca, has asserted that in Lake Como and other lakes lodge horrors unknown to modern biology - creatures that have miraculously survived millions of years of evolution. He claims he possesses scientific evidence and describes sightings as "absolutely trustworthy," so a local newspaper printed its idea of what the terrifying creature must look like.

After all, what is a lake without a monster? A lake that for so long has been the gilded

doorway to what another local author calls "the land of art, love, and dolce far niente."

EXPLORING LAKE COMO AND ITS VILLAS

With steep, thickly wooded slopes plunging into the lake's waters and a succession of charming towns and elegant villas dotting the shores. Lake Como offers a series of visual impressions of serene beauty. The lake's attractions can best be seen from the boats that ply its waters, providing transportation between the towns along its perimeter.

The Navigazione Lago di Como runs the public boat lines. In the city of Como, the company's office is at Piazza Cavour, on the lakeshore promenade. Service is frequent and boats run throughout the day. There is fast hydrofoil service, in addition to the regular boat service. Visitors can get off at any of the towns served by the boats, take time to explore the villages and then catch another boat to continue their tour of the lake.

Among the highlights of the western branch of the lake are stately villas, sach as Villa d'Este at Cernobbio and Villa del Balbianello at Lenno, the charming town of Bellagio, with more villas; the botanical gardens of Villa Carlotta at Tremezzo; and Comacina, the only large island in the lake. The eastern branch offers lovely lakeside scenery and, at Lecco, Villa Manzoni, a Neoclassic mansion where author Alessandro Manzoni spent much of his youth. The northern branch of Lake Como has some beatiful medieval churches, among them Santa Maria del Tiglio at Gravedona and the Abbey of Piona, near Colico.

Villa Olmo in Como has a lovely lakeside park. Open daily, extcept Sundays and holidays, year-round. Tel. 031-252443.

Villa Carlotta in Tremezzo, fronted by a terrace English garden, has a richly planted botanical garden. Open April 13 October 31. Tel. 0344-40405.

Villa Melzi d'Eril in Bellagio has lotvely pavillions and arbors on the lake and is known for its exotic plants. Park open March 28 - October 31. Tel. 031-950318.

Villa Serbelloni in Bellagio is owned by the Rockefeller Foundation: the park can be visited by appointment April 1 - Ottober 31. Tel. 031-950204.

Villa del Balbianello in Lenno can be reached only by boat, departing from Sala Comacina. The park can be visited Tuesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday and Sunday April 1 - October 31. On the first and last Sunday of the month it can be reached by land from Lenno. Tel. 0344-56110, 02 4693693.

OLD CHARM AND INTRIGUING CONTRASTS OF COMO

The old city of Como is to those who love it the most perfect gateway there could be to Italy's most beautiful, most romantic lake, sighed over by poets over the centuries. At night, young couples, hands clasped, dawdle along the endless promenade fitted around the bay like a horseshoe. The only sounds are the lapping of water and the occasional squawking of scooting ducks. White ferryboats tug at their moorings, impatient for the morning. Under the half-moon, the bay appears trapped between towering mountains that plunge into the water on either side as sheer as wails, adding a special thrill to the air.

The lake is a wiggly inverted letter "Y" cut into the thickly wooded foothills of the mighty Alps, close to the Swiss border, and the city of Como graces the foot of the letter's left leg. It is a trend-setting place, standing for revolutionary architecture from yesterday and today. Though, geographically, it is not far north of busy, prosaic Milan, in spirit it is light-years away. It has somehow retained, in unison with the shores of the lake, the same air of genteel, old-fashioned elegance and charm that so bewitched travelers from northern Europe - from Lord Byron to Stendhal - and was later transmuted into a balmy turn-of-the-century atmosphere. It boasts palatial lakeside hotels set on landscaped grounds, a dizzying cable car ride up to a panoramic view, parks, gravel paths, flower beds, tinkling fountains, shaded walks and an aura of easily borne wealth.

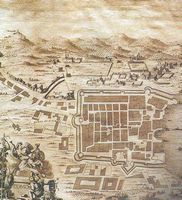

Como. An old map shows the layout of the walled city, with the regular grid

plan that is a signature of ancient Roman town planners. The modern city has

expanded beyond the walls, but this remains the core of Como's social and

civic life. The catherdral and the lakefront, center of the city's activities.

It has a whiff of the old French Riviera but is far more old Italy, since behind the grandiloquent hotels, within the silent, spotless and pedestrianized so-called Walled City, Como seems frozen in time, a dip into the 17th and 18th centuries, preserved utterly intact. One strolls down streets without sidewalks past straight rows of sober patrician dwellings with fanciful wrought-iron balconies, not a few of them completely adorned on the outside with painted, strictly geometrical designs. Mingled among them are more ostentatious Renaissance palazzi, once the strongholds of the city's warring medieval families such as the Rusca and the Vitani clans. You somehow sense they were not to be messed with, and a schooled sixth sense might also register another, sensation - for you are treading thoroughfares that follow exactly the layout of the garrison town of ancient Rome that Como once was, a settlement that only really came into its own under Julius Caesar, who, as commander of Cisalpine Gaul, settled a contingent of five hundred Greek slaves of noble birth here to lend it a touch of class. Vanished Roman walls also set the pattern for the doughty 11th-century walls of today, studded with towers. The most grandiose and severely spectacular is the tower of Porta Vittoria. And the classic format of the Roman house, with an inner courtyard, persists throughout the city as well. In other words, Como has Rome in its genes.

And the initial, mistaken, impression, may be that the past, rather than the present is what the people of Como, or the Comaschi, prefer. Take the shops, the cafés. A seemingly deliberate olde worlde quaintness clings to them. Doors are of fretted woodwork, colors are subdued. There is oak paneling, dainty lace covers cocktail tables, and the waitresses are solicitous mature ladies in lace collars and little pinafores. But then comes a surprise - the discovery of just how many exclusive shops display neat piles of expensive wares from Italy's top fashion houses especially ties and scarves, that are up-to-the-minute in design.

This is another Como, the mirror of a city that for nearly five hundred years bas been Italy's king in the manufacture of silk, the main source of its wealth, though now it prints and dyes the latest new artificial fibers as well, and has become, by extension, a huge display window for the entire trade. One expert says, "Como is an open-air boutique. People come here because they can find what they want." Another explains how economic survival hinges on keeping geared to the times and to fickle tastes. "We've got modernity in our DNA," he says.

And that provides the key to Como, for it is above all a frontier town, prone and quick to react to outside influences, kept modern because of its position, its lake being a spindly hyphen linking Italy to the whole of northern Europe, a conduit for thoughts and styles going both ways. And taking styles outward during the Middle Ages were men who made Como hugely famous, the so-called Masters of Como, a gifted clan of itinerant master builders, masons, sculptors, stonecutters and designers who turned their city into a hub from which then revolutionary Romanesque architecture radiated throughout medieval Europe.

The supreme symbol of this in Como is the most boldly poetic of the city's splendid Romanesque churches, 11th-century Sant'Abbondio, named after an early local bishop, seen as a remarkable feat of dovetailing - between northern Italian earthiness and the mysticism of introspective northern climes. Formidable and five naves wide, it has twin bell towers, eloquent with spiritual assertion and thought to be unique in Italy. Otherwise Sant'Abbondio is utterly homegrown. The classic semicircular apse, for instance, is a blaze of 14th-century frescoes, full of the placid grace of art in Umbria and Siena. Then there is the Romanesque church of San Fedele, with its resplendent rose window and an interior that is stunningly novel, medieval marvel with upper loggias and galleries. And opposite the church you will find two well preserved timbered dwellings of the 16th century.

The church of San Fedele. Framed by the arch and the sign of a popular cafe'

The church is one of Como's several striking medieval churches.

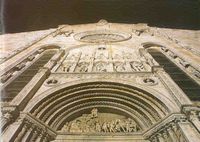

The Masters of Como came into their own with maximum vividness when fashioning Como's extraordinary cathedral. Again to step inside is to behold the loftiness, the soaring pillars and muscular cross-vaulting far more typical, on a smaller scale, of the great Gothic churches of northern Europe - those of Chartres, Cologne and York - than of Italy's churches. But then peer up the spectacular, racy facade, turned by the Masters into an exuberant yet stylized portrait gallery that could not be more Italian. They brought it to life in the 15th century, bringing about a miraculous blend of Lombard, late Gothic and Renaissance styles, and "peopled" it with precisely sculpted little figures. The figures are biblical personages and saints, mostly stacked one on top of the other within slim vertical pilasters that elegantly divide the facades into fields that look like tubes, topped by curious pinnacles or minispires so proliferous that one onlooker exclaimed: "It's like Kremlin!" Yet two of the figures, sitting in theatrical "boxes" on either side of the main portal, are totally pagan, placed there nonetheless out of local pride in Como's two most illustrious sons.

The cathedral. A bird's-eye view of Como's cathedral and the tiled rooftops

in the city's heart. Completed in 1700s, the cathedral undergo numerous

architectural transformations during its long life. Begun in the 1300s,

it is the work of so-called Masters of Como, sculptors, stonecutters and

church builders. It blends Northern Gotic with Lombard and Renaissance styles.

They are Pliny the Elder, the 1st-century Roman writer on natural history who perished while studying the eruption of Vesuvius that wiped out Pompeii in A.D. 79, and Pliny the Younger, his nephew and adopted son, a celebrated letter writer, who described his zealous uncle as wearing a pillow around his head against falling debris, struggling to take notes among lethal fumes that finally overcame him. Both had estates on the lake and it is said of the Younger that despite his popularity in Rome, Como held first place in his heart. He entertained a circle of friends in various villas and endowed the city with a rich library. Joined to the cathedral like a rib, incidentally, is the dwarfed remnant of an old courthouse, called the Broletto, that was pulled down to make way for the church, perhaps left there on the strength of its telling gracefulness, the gentle poise of upper chambers above a flawless arcade, all in warm marble.

Another famous son of Como falled to gain a place of honor on the-cathedral's facade because of a time difference. He was Alessandro Volta, the scientist who opened up a new era in electrical research and created a huge sensation in 1800 with his invention of the battery. Napoleon Bonaparte summoned him to Paris to pin a medal on him for it. Earlier, he had discovered methane gas. Today, Como remembers him instead through a fine statue in a main square and a "Temple," a Neoclassical-style monument built in his honor in 1927 on the lakefront. The Temple's interior is a vast circular hall topped by a dome, and it is a showcase of Volta's experiments and inventions.

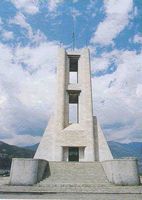

Monument to Alessandro Volta, the most illustrious native son of Como.

Oddly, however the artistic openness of Como finds no counterpart in the character of its people and, more oddly still, within minutes of meeting you, they will tell you about how reserved and closed they are. One acknowledged: "We are as enclosed within ourselves as our lake is within its mountains." Just as blunt, though, is their honesty, and their appetite for hard work is proverbial, which explains why they are so obviously well-off. One selfmade man even proclaimed, "We prefer work to play."

Perhaps the answer lies in grim memories of Como's blackest years spent under Spanish dominion, when the dreaded Inquisition set about stamping out a strong local proclivity for superstition and witchcraft with "barbarous severity," as an English traveler testified. He said executions of alkleged witches were so frequent that "stake, gibbet and the implements of torture became part of the firniture of the Cathedral Square." A present-day teacher confirmed: "Witches were burned by the hundred for dancing with the devil, for instance."

The people of Como stuck to their independence of spirit, and fought hard for it when saddled with the next occupier - Austria in the 19th century. They rebelled. It was in Como that some of Italy's first subversive secret societies were born, the seeds of the long struggle for unity. Printing presses in Como were crucial in spreading anti-Austrian propaganda throughout Italy, and in 1848, a five-day insurrection broke out in Como. And the next year citizens scrapped side by side with Garibaldi during a revolution in Rome. They rang church bells and feasted when he occupied Como in 1859, and then joined him on his triumphant expedition to Sicily, which set the struggle for Italy's unification on the road to triumph. Many lost their lives.

Como witnessed another revolution in the 1930s, its outcome starkly in evidence today, since upheaval this time was again in the realm of architecture. The frontier city played a role, becoming, thanks to a great artist, the funnel through which so-called rationalism seeped into Italy from Germany and France. Guido Marinucci, former professor of architecture at Rome University, defined the movement as one that sought to supplant the then prevailing taste for fantasy in new buildings, especially apparent, he said, in German Expressionism, through a return to principles of rationality. "It was anticonventional, and had to do with a new dynamism centered on simplicity and clarity." The pathfinder, the artist who in Como engineered this quiter break with the past, was Giuseppe Terragni, a great figure in the history of Italian architecture. He gave rationalism an exciting new, Italian, look, but was greeted by jeers and cries of outrage.

Among other of his dramatic creations in Como is a sky-piercing war memorial on the edge of the lake, an adventurous "lighthouse" bursting with upward thrust, now the city's most prominent landmark. But Terragni is said to have committed suicide, a victim of philistine incomprehension. Now his war memorial is used as a handy navigational aid by small flying boats that all day wheel and weave above the lake, then landing on the lake in front of the city amid hissing clouds of spray, just as the ducks do. But perhaps the monument serves another purpose as a tribute to Como as a city of pioneers.

The war memorial. This 1993 monument on the lakefront is a strong statement

of Rationalist architectural tenets. It was designed by Giuseppe Terragni

Flying boats provide quick transportation around the lake and breathtaking views of the scenery. The marina at Como is safe haven for sailboats.